Like and share for this terminally ill baby! Like and share if you think cats are cute! Like and share if you think nonces should be hanged! Like and share if you remember the ’90s! Like and share if you have two thumbs! I bet no one will share this random photo of a 90-year-old man I found on Google.

Sigh. What’s this? Ah, it’s a six-year-old, vaguely racist meme that an old colleague shared. I scroll on.

So sick of it :(

U ok hun? PM me xx.

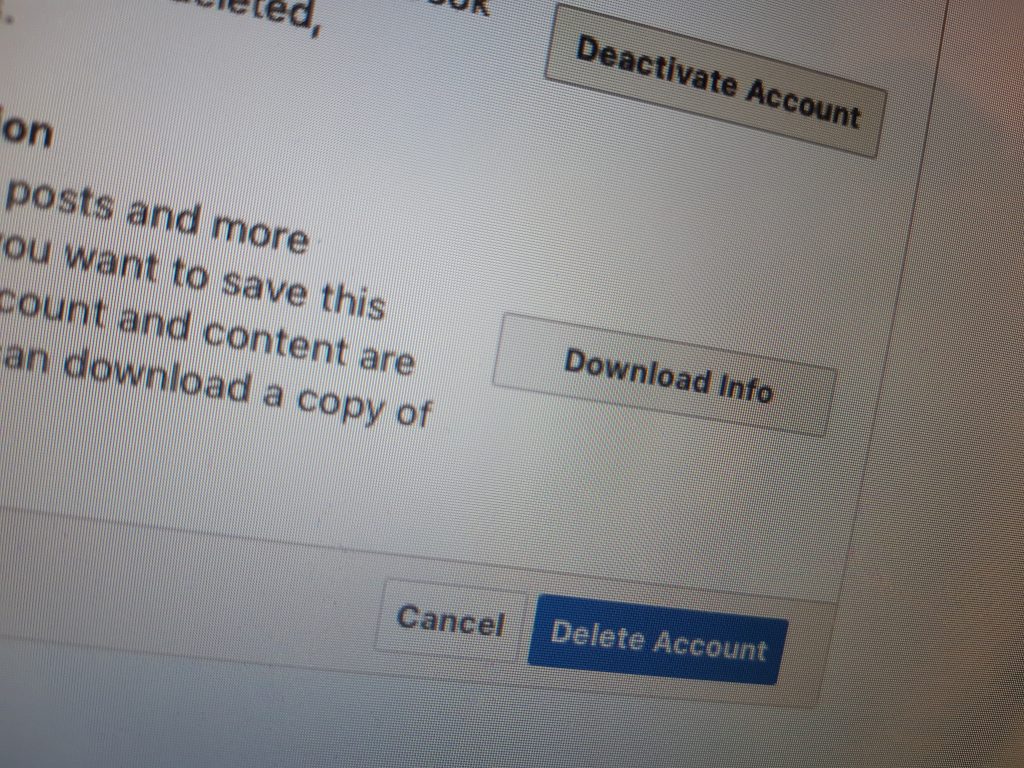

We’re all familiar with such repetitive posts filling our Facebook feed. But, of course, we can just unfollow, unfriend or block those responsible for the most trifling incursions into our newsfeed. The Zuck gave us lots of tools with which to moderate the content which the Facebook algorithms regurgitate onto our computer screens. We can unfollow the guy who updates us with the minutiae of his day without causing him offence by unfriending him. We can choose who takes priority in our newsfeed (not the ex-colleague whose friend request you acquiesced, who turned out to be a poster of weird conspiracy theories). But to what end? We may end up with less of the trifling clickbait and vagueposts in our newsfeeds, but when these are replaced with posts curated strictly according to our narrow, inflexible tastes, we see the vague posts and clickbait replaced by equally as tiring posts centred around our own hobbies or political views. My newsfeed, after an afternoon of carefully screening the most tiresome of whingers, clickbait sharers and day-to-day autobiographers, became an infinite feed of communist memes and Guardian articles. Different theme, equally as mundane. My tastes and yours may be different. But whether it’s communist memes, weird conspiracy theories or something in between, echo chambers are not interesting. Facebook should open us up to the world, but it encourages us to be inward-looking and closed. Facebook reinforces our worst behaviours, attitudes, and poorly researched opinions by showing our posts to a small group of people who we have specially selected because they will commend us for our vices. Perhaps there are ways to make Facebook work, but I chose to quit.

I endeavoured to begin retirement from the part time job I had held from the age of fourteen: PR manager for Jack Pepin Inc., I had learned a lot in those seven years on the job. I had become an expert in choosing the right picture for maximum likeage (beachfront portraits replacing low angle selfies in poorly lit rooms); in the correct protocol for conducting comment section arguments (don’t); and in achieving the perfect frequency of posting to avoid boring my friends whilst still ensuring that they read as many of my thoughts, musings, and stolen content as possible.

With newfound time on my hands, and my mind no longer preoccupied with keeping up appearances, I had time to scratch another itch. I booted up Tinder for the first time in a while. Ah, a problem: having been obliged to create my Tinder account using the Zuck Book, I couldn’t use Tinder without reactivating my blue and white blog, and all of the associated little dopamine hits quantified and digitally categorised and stored away as “likes”. Of course, it immediately occurred to me that a slew of websites which I visit occasionally would be out of bounds to me. Facebook, Google, and Twitter have come to serve as convenient doormen for all of our online accounts. Social logins are quick and simple. The alternative to clicking on your little avatar is to create an account by filling out a form full of information the website shouldn’t need, and remembering yet another unique password (with at least three uppercase letters; at least two lowercase letters, except for on Sundays when three lowercase letters are required, unless the new moon rose on the last Tuesday of the previous month, in which case the number of lowercase letters required is a function of the quantum decay of Uranium; and at least one special character), and, of course, the next time you use this website you won’t have a clue which variation of your standard password you used to fit the constraints. So of course we use the shortcut provided by our favoured social network.

As is often the case, the easy option has negative consequences in the long term. It should go without saying that the blue-thumbed corporation anticipated the hassle I would cause myself by deactivating my account. Friendface knows that anchoring its roots throughout our entire online world, into all the websites we use, dissuades us from leaving. Social networks ought to hold our attention by providing a platform for us to find quality content which entertains or educates us. They should provide a useful, intuitive user interface, and video players which work to our needs, not to manipulate us (looking at you, Facebook and Netflix). But if social networks retain our custom by dangling the keys to all of our accounts in front of our faces, we have a disincentive to leave a social network which may not be striving to high standards. Social networks must maintain their user base by providing a quality product, not by coercion.

Of course, Facebook gains more from social logins than just customer loyalty. It operates a bidirectional motorway of customers’ personal information between itself and its partner websites. Since the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which proved that Facebook’s entire data protection policy was based on nothing more than a promise by third-party developers to play nice, the information has been limited by default to a user’s name, email address and birthday—but other data, including all posts, can be accessed with the permission of Facebook. With virtually all of the most popular websites offering the option to log in with Facebook, that’s a lot of websites who can access your data.

Taylor Hughes, co-founder of social network Cluster, explains that bugs in the code, and poor, out-of-date user manuals diminish the efficiency of social logins for developers. So what’s the benefit to the websites who use social logins, if not convenience? Gigya, a platform that provides social login tools for websites, reports that 20% of websites that use its tools see a 50% increase in registrations by allowing social logins. It also found that people are less likely to abandon their shopping basket when they don’t have to undergo trial by ordeal to create an account.

“Surely,” you might say, “everyone benefits from social logins: small websites grow their user base more quickly with easier signups, users don’t have to remember another password, and Facebook gains more revenue from targeting adverts more appropriately.”

Well, perhaps. But a good consumer should be in control. As things stand, Facebook uses its custodianship of our online personalities to influence us. Websites use the convenience of a one-click sign-in tool to convince us to hand over our personal information, and once again we, consumers, are out of control. This isn’t to say that we should be paranoid privacy extremists. After all, we freely give away our personal information when we sign up to Facebook in the first place, but we should understand the power that we grant Facebook when we use it as a portal to our entire online world. We should understand the value of our data to it, and whether we are getting a fair exchange.