In 2009, as I longingly browsed eBay for an iPhone 3GS with no intention to purchase one with my €5 weekly pocket money, I came across a phone at a shockingly low price, yet with every resemblance to the phone I yearned for. I had come across the Sciphone, made by a Chinese company with a flagrant disregard for patent law, and whose business model was to flood the market with iPhone lookalikes. Of course, the phones had obsolete resistive touchscreens rather than the preferred capacitive type, no functioning app store, little memory, and little else besides to truly set them apart from a feature phone. The Sciphone was a smartphone in appearance only. Sadly, this was to be my first smartphone. Perhaps by accident, perhaps not, it would snap in half in the pocket of my particularly tight Tommy Hilfiger jeans as I bent over. Woops.

Then there were the gimmicks. Projectors, handwriting recognition (astonishingly, this is a slower method of typing than using the keyboard of your old flip phone), smaller than a credit card, phones with cigarette lighters (“fag phone” would have been a catchy name, I think. The marketers were clearly asleep). These cheap, underpowered phones—named shanzhai by the Chinese, which translates to “bandit”—which are often reminiscent of Samsung and Apple’s flagship phones, were predominantly produced in Shenzhen, a Special Economic Zone on China’s south coast. Just 40 years ago, Shenzhen was a market town, home to thirty thousand people. This all changed in the 1980s, when the deregulated area—think wild west, but in the digital age, and there aren’t any sex robots either—became a thriving agar pot for the unscrupulous trailblazers of China’s fast-growing manufacturing industry. It does, however, also house companies behind the more well-known phones—Foxconn, one of Apple’s largest suppliers, has its largest factory in Shenzhen. Its factory is referred to as a city by its employees: tens of thousands of workers live on site, which gives need for their own town centre, hospital, and fire department. With factory cities producing tech products around the clock, it’s no wonder Shenzhen has given birth to a new generation of Chinese smartphones: a generation eager to ditch the tainted image of Chinese tech; a generation not just made in China, but designed in China too.

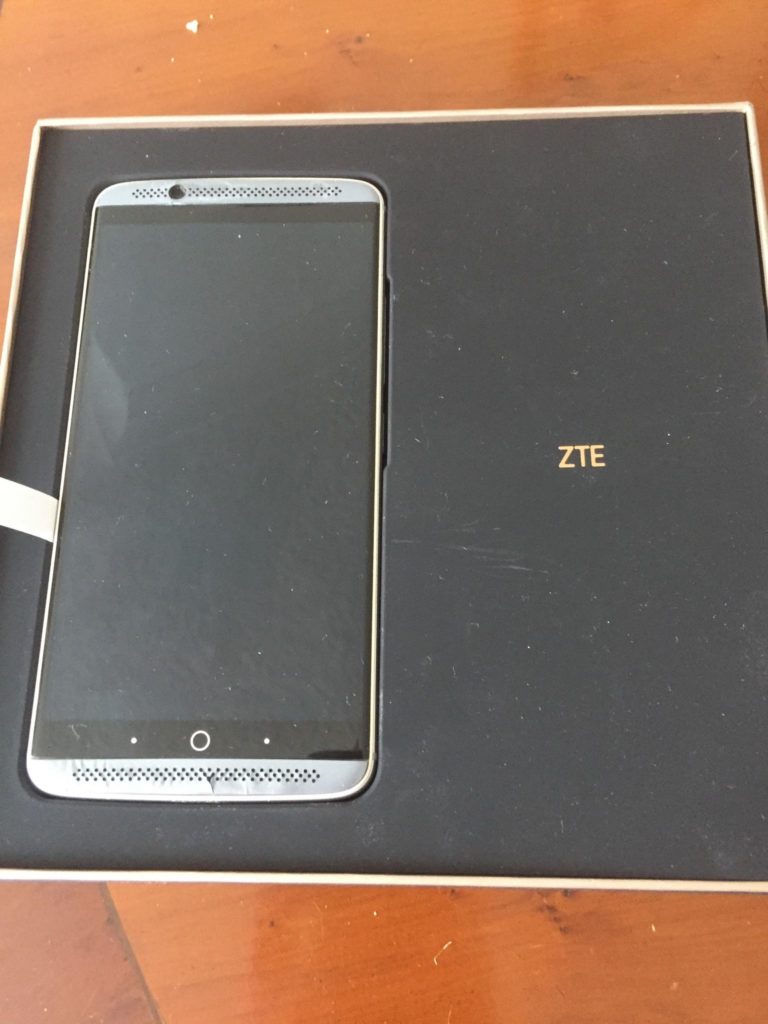

Out of the shady factories of Shenzhen, where copyright laws are given similar consideration as tourists give to escalator etiquette, some new, legitimate, suit-and-tie-wearing, tax-paying titans have arisen. We have become familiar with some over the last five years—One Plus, Huawei, HTC—and others are poised to become big, such as ZTE and Xiaomi.

OnePlus has taken the UK by storm, despite being founded less than 5 years ago. Huawei, known in the past for making mobile broadband dongles, are now well-known for their Honor and Mate range of smartphones. But ZTE, Xiaomi, Oppo Mobile, Alcatel, Gionee, and Tecno are among the biggest smartphone manufacturers in the world, and I’ll bet you haven’t heard of one of them. They all arose from China’s Special Economic Zones and, with its population at a staggering 1.4 billion, there’s no need for any of these brands to make a great effort to sell outside of China. But, given their increasingly competitive offerings, perhaps Mohammed must go to the mountain.

For the last year, I’ve been using the ZTE Axon 7 (which directly succeeded the ZTE Axon, but came out the year the iPhone 7 was launched. These marketers were not asleep at the wheel). Because the phone isn’t available in UK stores, it must be imported from China, and can potentially incur a 20% charge at the UK border, payable to Her Majesty’s representatives in the tax department. The importers helpfully, however, mark the goods as “gifts”, which are exempt from this tax. For £323, I received a phone packed in a meticulously designed box with a pair of earphones and a USB-C cable. The phone featured the latest Snapdragon processor, 4GB of RAM and 64GB of storage. Apps launched faster than the light could travel from the 3.7 megapixels to my face—that’s almost twice as many pixels as you’ll get on a similarly sized iPhone 7 Plus—with animations as smooth as butter-on-a-hot-day. The speed, as is inevitable, dropped with time, but the phone came with NFC, Dolby Atmos speakers, and a fantastic resolution—pretty great for less than half the price of an iPhone 7 Plus. In the warranty booklet, to my pleasure, I read that I would receive one free screen replacement if needed. This is more or less a free gift of £100, right? What is it they say about that which sounds too good to be true?

When the time came to claim this courtesy—my phone having become dislodged from my limp hand by an inebriated reveller and having become acquainted with the concrete floor of a warehouse in Walthamstow last New Year’s Eve—I discovered (after a couple of days of sobering up) that I couldn’t reach any representative of ZTE. No telephone number, no email address. I came across some fellow wanderers in some of the remoter parts of the internet during this wild goose chase who claimed they had successfully contacted ZTE, but were informed that no such offer had ever existed. So there lies the rub: when problems arise, you can’t phone a call centre or walk into a high street store and ask to speak to the manager, thank you very much, as you can with the smartphone giants we’re used to. Because these phones must be bought through a Chinese, third-party importer, basic consumer protection laws, such as the right to a refund, don’t apply. Clearly, a great deal of the money we pay to Apple, Samsung, HTC and One Plus funds customer service and generous returns policies. These opportunity costs have to be factored in when opting for a phone sold by third-party importers. In the end, I had to pay a whopping £100 just for the replacement screen, let alone the cost of labour, and I waited several weeks for the replacement to be shipped from China.

The Chinese market has become fantastically competitive, driven by a huge amount of competition. One of my prior smartphones was also made by ZTE. It was underpowered, crashed every few hours, and it’s slow-to-start apps cost me a ton of lost photo opportunities. ZTE has transformed since then. Their business structure is similar to Apple’s—just one or two products per category—and their devices are comparable in quality—the Axon 7 was a big upgrade from my only-slightly-older iPhone 6. Of course, with their cheeky, fanciful free repair offer, they haven’t entirely departed from their shanzhai origins.

While established brands like HTC, OnePlus and Huawei compete strongly on the UK’s high streets, and brands like ZTE and Xiaomi offer astonishingly good value if you’re willing to flout (or have flouted on your behalf) UK customs tax and wait a few weeks for delivery, it must be said that they haven’t yet come close to conquering the British market. Apple holds a striking 48% of the British market, and Korean Samsung holds most of the rest. But, I bid you, let the Chinese earn your respect. Their phones are no longer underpowered, and you won’t find any hidden utility belt items hidden under the bezel to sweeten the deal. If companies like Huawei and ZTE don’t have their international ambitions thwarted by the trade war between the US and China, and if Apple doesn’t monopolise the Chinese market as it has the British market, the Chinese smartphone makers will go from strength to strength.